The Anatomy of Economic Stress & Trauma

How fight, flight, freeze and fawn show up in money, work and relationships

This article is a deep dive into what economic trauma is, and will serve as a foundation for the newsletter before I get into a more systematic, change-focused analysis. It should go without saying that the topics might be triggering - although I’m sure if you’re already reading this, you’re perhaps already mentally prepared to dive into what I’m about to explore.

Money is an emotionally loaded subject for many of us around the world. For many, it may represent a forever unachievable state of abundance or emotional security. It could also mean memories of hardship and a lack of agency that we’ll do anything to never return to. It could be the source of conflict between two spouses, who just can’t fathom no matter how hard they try, how the other could have such unbelievable spending habits. Money can be a source of insecurity, of shame, a way of symbolizing that we belong with the people around us. It could also mean pride or glory, or a way of showing love and care for the people we love. It could mean every difference between our permission to let ourselves take a much needed holiday, or to put all our eggs into one investment basket that could very well completely backfire. And all well intended, for the dreams of a better future.

However, the frame of thinking of money and the economy as a rational & un-emotional subject still dominates most of public awareness today. We’re intellectually detached from how it originated as a tool of division historically created to force communities into a subordinate role within broader colonial power structures. But money wasn’t just successful because of its power for external division and control - it has also successfully hacked into our minds. We project values onto money, work and status, because it is heavily tied with survival. And because it is still to this day so interdependent with our path to wellbeing, it seeps into the collective fabric of how we see ourselves and behave.

So much of ‘success’ in the current societal paradigm demands us to have a secure relationship with money and our place in the economy, with little conversation about how our stress responses show up, individually or collectively. If we looked closer into our own psychological undercurrents of why things occur, and how systems around us enforce that - could we imagine a more deeper, profound change?

Trauma is a Survival Response

At its core, trauma is a physiological survival response that our brains have evolved to invoke to help us navigate threatening situations. It is a similar protection mechanism that wild animals have, a function to instinctively remember what other animals and contexts would be unsafe.

If a large threatening animal such as a bear approaches us in the wild, our brains have evolved over thousands of years to help us escape it. Our nervous system fires up with cortisol and energy, our hearts beat fast, prepping us to decide how to escape danger. Once we’ve successfully gotten away, our initial stress slowly calms away as we’re regrouped with our community members. We’ll probably talk of the bear and its presence, and warn our friends and family members not to get close, and they’ll celebrate our return. If we were really badly hurt by this bear, or someone was killed by it, the impact of this memory will be etched onto our memories even more instinctively. We might stay up for nights mourning the brutality of this person’s death, or continue to feel hyper-vigilant if the bushes start rustling in the middle of the night. In a different context, trauma has always served an intelligent purpose - to remember what is dangerous in order to survive.

But what happens when the danger isn’t a threatening bear? Human societies have evolved rapidly, but our biological responses have largely remained the same throughout thousands of years. What can be registered as unsafe for us moves and changes as the world around us shifts. The bear that hurts us today, can very well be being shunned by others for not having a high earning job. It can also be the chronic stress of not being able to pay the bills and the sacrifices that were made during the process - the people we had to leave, the dreams we had to give up, the suffering all around us we saw.

Note: Not every stressful experience integrates into the body as trauma. When the right interventions are implemented, a bad experience can just stay a bad experience, far in the past and not affecting our present. I’ll be exploring this later on.

Financial & Economic Trauma

“Traumatic experiences cause a somatic contraction and “shaping” that becomes unresponsive to current time experience. Rather, the psychology, physiology, and relationally all remain organized around protecting from the same or a similar harm, without taking in new information. We become organized for danger, abandonment, and humiliation.”

- Staci Haines, The Politics of Trauma

Economic trauma is a name for a biological, neurological and physiological survival response, that comes out of experiencing extended periods of economic danger, or not having our needs met over a long period of time. The impacts of it are likely far reaching and wide - researcher Dr. Galen Buckwalter found that nearly one in four Americans and one in three millennials suffer from PTSD-like symptoms caused by financially induced stress. However, its impacts on a global context are still under-researched.

As traumatic experiences organize us against danger, economic trauma may show up as insecure narratives we have about our relationship to money, or our place in the workplace and society.

Beliefs & Narratives

• “No matter how much money I have, I still don’t feel I have enough.”

• “Money doesn’t come easily to me”

• “I’m resentful & jealous of people who have money”

• “If I don’t have enough money, I am on my own when crisis strikes”

• “I make good money, but I have no idea how I keep losing it every month. I just keep spending.”

• “My parents suffered, and I don’t want to suffer like them, so I need to do everything to be secure at all costs”

• “If my children don’t choose a lucrative career, they’re not going to survive”

• “I need to go above and beyond in the workplace, or else I’m not going to be accepted”

Note: These are personal narratives, but on a macro level, they manifest themselves cultural norms, when there is collective belief and normalization.

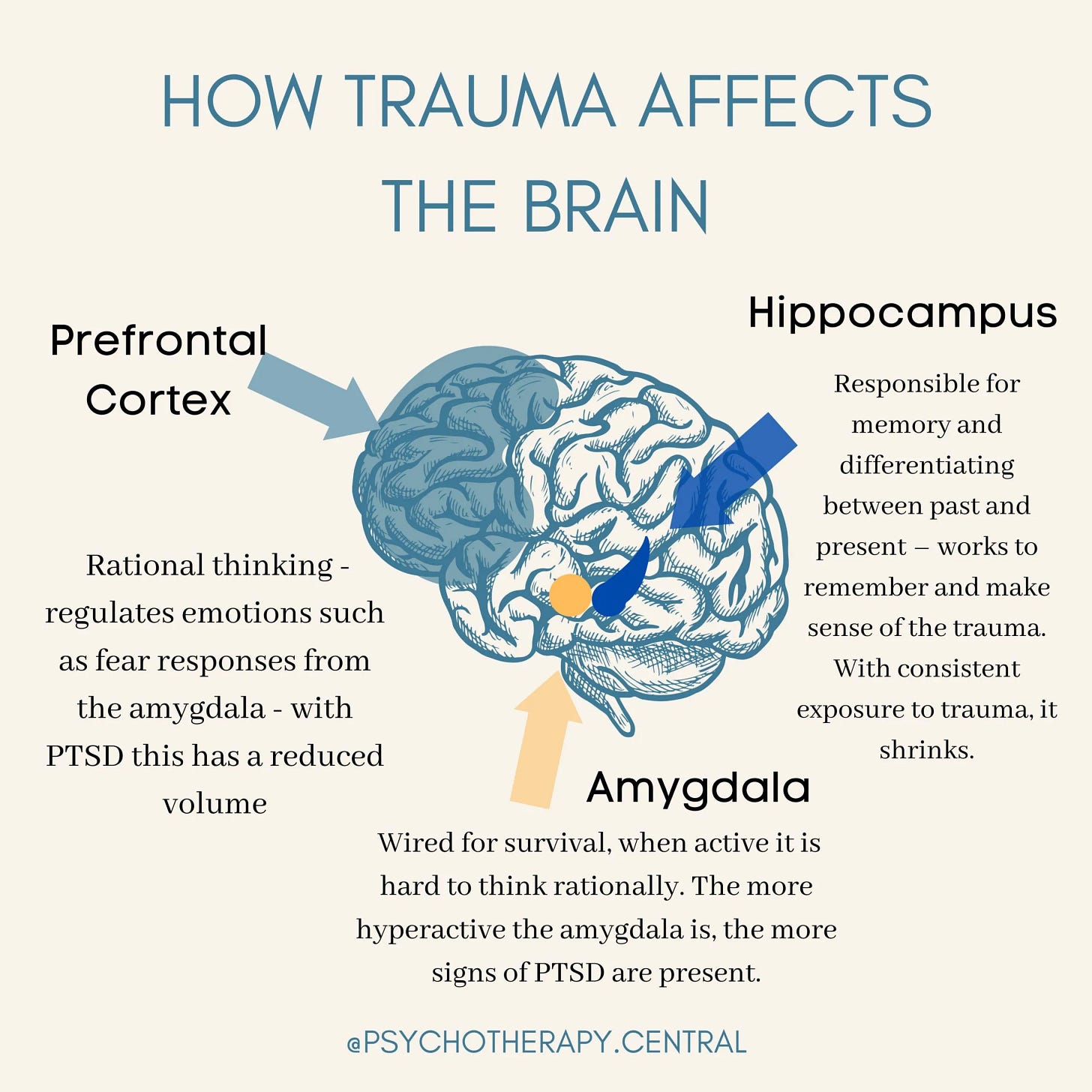

Impact on Brain

Trauma, just like chronic stress, also has an impact on our behaviors because of the way it affects our brain.

Emotional Regulation: The amygdala, which stores memory, becomes more sensitive when severe or chronic trauma occurs. It is the part of the brain that activates fight or flight, thus making emotional regulation during times of stress harder for us

Long Term Thinking & Problem Solving: The pre-frontal cortex’s ability to manage problems, learn and plan shrinks.

Risk Adverse & Driven Behavior: Without emotional response flexibility, the traumatized person can likely be more impulsive, or hyper-vigilant

Higher Likelihood of Health Issues: Gabor & Daniel Maté’s The Myth of Normal explores how trauma is connected to global health epidemics and addiction

Stress Responses Stuck In Time

There are many ways trauma shows up, but one of the most obvious ways is through physiological stress responses. When we’re confronted with the threatening bear, our nervous system instinctively fires a response to help us prep for danger. These responses are known as fight, flight, freeze or fawn.

Here’s a squirrel going into a Freeze response:

Just like the squirrel, these stress responses that can kick in, even involuntarily, while close to a perceived scary human. They will feel almost ‘automatic’, ‘instinctive’ or ‘trancelike’ - reacting impulsively based on situations. The distinction with a post-traumatic stress response is whether we’re responding to current threats, or situations that remind us of threats from the past. Put simply - the distinction between the two is whether there’s really a bear in front of us, or something that reminds us deeply of the bear. Is impending poverty a real risk, or are we responding based off of memory? Is everyone who disagrees with us the same bully that tore us down?

Trauma integrates into our bodies when the stress response we’ve initially exerted becomes stuck with no where to go. If there isn’t an actual bear to escape from, it’s unintuitive for us to know how exactly to calm down. This survival energy whizzes through the body, while the person is unaware of how to channel it. Instead, it makes them anxious, paranoid, shut down or activated towards misdirected goals. The formerly intelligent survival instinct starts hurting us, and hurting others around us.

But these survival responses are not set in stone, and we can change how we respond. In order to do so, we have to begin recognizing how they show up.

Fight

The fight response is triggered when we think that the bear is a threat that we have the capacity to overpower. It’s a sudden rush of anger and power that helps us rise up to the challenge we’re facing. Our perceptions become sharp, our attention focused on maintaining control so we can protect ourselves and the ones we love around us. However, because it is inherently connected with a capacity to inflict violence, it also has the capacity to be one of the most harmful stress responses in relationships.

Mental & Emotional

Chronic anger, irritability & frustration

Lashing out, sudden outbursts

Overthinking cycles

‘Victim’ thinking - “They’re out to hurt me, I must fight back”

Narcissism

Possible Behaviors

Threatening or enacting violent behavior

Money used as a tool of manipulation and control

Impulsive investing to compensate for losses

Concrete threats or actions such as, taking legal action

Relationships & At The Workplace

Self entitlement - “I am right, you are wrong”

Excessive defensiveness

Excessive competitiveness

Excessive micromanagement of others

Demanding & controlling

Blaming, deflecting responsibility

Not listen to others’ opinions

Bullying, assault, physical & emotional violence

Flight

The flight response is triggered when we think that the bear is a threat more powerful than us. It’s a sudden energy to run as fast as we can, so we’re faraway from the risk. It can drive up adrenaline, make our hearts beat fast, so we’re faster than we ever usually are. However, the flight response can also manifest as mental escape, if it feels like what we’re confronted with is too daunting to face. Thus, it can also manifest for us mentally and emotionally as avoidance & distraction.

Mental & Emotional

Avoidance - “this is too scary to face”

Excessive distraction & procrastination

Fantastical & delusional thinking

Preoccupation and anxiety

Inability to relax

Restlessness & hyperactivity

Possible Behaviors

Impulse purchasing & financial decision-making

Pleasure seeking and addiction to consumerism

Excessive content consumption

Selling all assets impulsively

Relationships & At The Workplace

Procrastination

Perfectionism

Workaholism

Conflict avoidance

“Hiding” through disengagement

Freeze

The freeze response is activated when we believe we can neither overpower the bear, or outrun it. Our bodies go into shutdown, and stay frozen in silence, so that we may be perceived as non-threatening to the bear itself. The freeze response is unlike the sudden rush of energy in fight or flight, and instead manifests as ‘smallness’.

The freeze response may be hard to spot, as it also exists in high functioning and high performing people. The hallmark is of it is disassociation from our emotions and physical body.

Mental & Emotional

Disassociation

Disconnection from Self, Emotions & Body

Apathy

Self Numbing

Self Neglect

Possible Behaviors:

Financial avoidance

Choice paralysis - inability to make decisions for self

Giving up on managing work & personal finance

Giving up on taking care of personal health

Relationships & At The Workplace

Isolation from others

Relationship neglect

Stuck & unmotivated

‘Victim mentality’ & helplessness - “I can’t do it”

Fawn

The fawn response is the least known stress response. It is also possibly the hardest to see, as it doesn’t look so abnormal initially. Some derogatory synonyms for this response can look like calling someone a ‘pushover’ or ‘people pleaser’ - which accurately describes what this stress response tries to achieve. It is activated when we believe we can somehow befriend, appease or control the threat in front of us, in order to escape the threat to ourselves.

Mental & Emotional

Lack of personal boundaries - difficulty saying ‘no’

Denial or disconnection with personal needs, desires, fears and complaints

Exhaustion from overthinking and anxiety on how to not cause conflict

Focused on external validation

Possible Behaviors:

Lack of financial self worth: Difficulty making the case for self to earn more money

Lack of financial boundaries: Overspending on others

Choice paralysis - “I don’t know what I want, only what others do”

Relationships & At The Workplace

People pleasing

Turning a blind eye to injustice to maintain personal safety

Over-apologizing

Inability to stand up for self

Abandoning own needs to serve others

Trying to fix others

Codependency

Distrustful of others

Many people in the world are simultaneously responding to both currently existing threats and threats from the past. Doing trauma-informed work means developing the literacy on how these stress responses show up - and thinking about how our relationships, environment, tools & culture encourage or normalize it. Once we learn to spot it in ourselves and others, how we respond means all the difference.

How we respond to economic stress & trauma makes all the difference.

Economic stress and trauma is a heavy reality for so many in the world. But it is not a pre-determined and forever carved out path. There is a reason therapeutic and community interventions are so effective - because we, innately, can change.

Although stress and trauma responses can cause damage to ourselves and the people around us when sustained, we are capable of repairing the conflict it’s created within us internally and externally. Awareness, personal, community & systematic interventions can make a huge amount of difference in changing the way we react. We can choose differently, use tools in a healthier way. We can help the people around us in social and work environments know how to work with how we are. We can integrate healthier narratives to live more fulfilling lives. I’ll be exploring these things in my next articles.

My hope is to make economic stress and trauma concrete for you - and that it’ll incite deeper reflection into your own life, your relationship to others, and if applicable, to the organisations and work you find yourself doing.

If this topic really resonated with you and you want to go deeper immediately, there is a myriad of resources online about fight, flight, freeze and fawn generally. You can look into both personal and relationship specific resources.

If you’re looking for something money-specific, I love looking at the Trauma of Money course and resources. There are also a growing availability of trauma-informed financial therapists, as this topic slowly gets into public discourse.